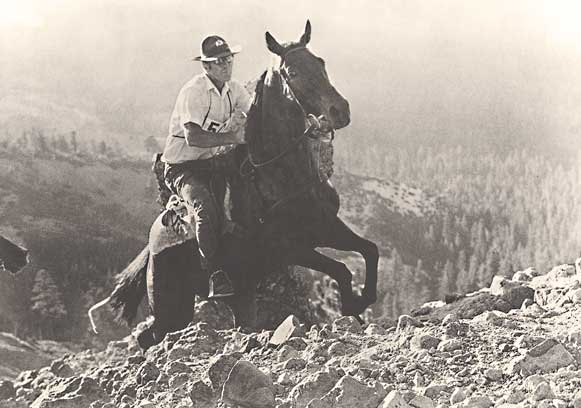

As one might expect, since the Western States Endurance Run (WSER) evolved from the Western States Trail Ride (a.k.a. The Tevis Cup ride) – after Gordy Ainsleigh started and finished the 1974 ride without a horse – many of the traditions from the horse race found their way into the run. There’s the 5 a.m. start, the silver belt buckles for sub-24 hour finishers, an absolute cut-off finish time, perpetual cup trophies (Wendell Robie and Drucilla Barner) for the winners, medical checks where runners can be “pulled” from the race, etc. And it’s interesting how many of these traditions are now pretty much the norm for all 100-mile runs even if they don’t make much sense today. For example, I think they’re cool and I’m proud of my collection of 100-mile belt buckles, but I’ve never worn one and don’t expect to (6/18/12 update: I have been wearing my buckles regularly now – see youtube video of how they are made). There is one notable exception that didn’t make its way into the run and that is the Haggin Cup trophy.

Don’t know what the Haggin Cup trophy is? I didn’t either until a few years ago. The Western States Trail Ride, which began in 1955 by Wendell Robie as a “ride” not a “race,” started becoming especially competitive after the first Tevis Cup trophy was awarded to the fastest finisher in 1959. With increasing attention from groups like the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA), which argued that the ride threatened the health of the horses by allowing them to be ridden to exhaustion and even death, an award was created to recognize the horse that arrived at the finish in “the most superior physical condition.”

Dr. Richard Barsaleau, a veterinarian who joined the race in 1961, was instrumental in creating this distinction, which he saw as an objective award that would recognize horsemanship, conditioning and respect for the health of the mounts. But it would also honor a great performance. Starting in 1964 the top ten horses would be judged for the Haggin Cup. In her book, “The Tevis Cup: To Finish is to Win,” author Marnye Langer wrote:

“Many people, especially noted horsemen, have come to regard the Haggin Cup as the most prestigious honor one can earn, and the award remains unique in both the sport of endurance and other equestrian pursuits as well.”

It’s rare to win both the Tevis and Haggin cups. Since 1964, there have been 43 winners of the Haggin Cup, but only six of those riders have also taken home the Tevis Cup the same year.

Should we have a similar award for the WSER? Maybe the Dr. Bob Lind Cup? We could compile the CPK levels, weight change from start to finish, blood pressure, pulse, condition of feet/blisters and other indicators from the top ten men and women. Runners would be eliminated from judging if they received an IV or were admitted to the hospital.

I know the race already has a long awards ceremony, and there are those who will say offering this kind of recognition would simply not be feasible. But even if we don’t implement such an award, I think it can be useful to consider such a prize. Imagining what it would take to win this distinction, makes us think about all the ways we push ourselves at WS and at 100-mile races in general. It makes us ask about the difference between good pushing and destructive pushing. Unlike riders who can push their horses, we runners push ourselves. We decide whether to continue grinding it out or whether to back off when things get really hard. For many of us, that is why we run 100 milers.

Andy Jones-Wilkins, a five-time WS finisher with 21 total 100-mile finishes says, “pushing myself hard at the end is what makes the experience so meaningful and ultimately difficult.” I agree with AJW. Much of the joy I get from running 100-mile races is pushing when the physical and mental load is tremendous. We get to tap into a drive or mental tenacity that is seldom tested in regular life. And we honor, respect and encourage runners to be mentally strong and persevere. As a volunteer or crew member, what do we do when a runner comes into Michigan Bluff exhausted, struggling and wanting to quit? We say, “Fix your problems and get heading to Auburn.” As a runner, that’s exactly what I want aid station volunteers, my crew, and my pacer to do. And it is what I expect of myself.

But what if we push too hard? What if we damage ourselves to the point where we end up in the hospital or worse? AJW knows about pushing too hard as he ended up in the hospital with renal failure after the 2004 Angeles Crest 100. Brian Morrison also knows about pushing too hard . “The scary thing,” Morrison writes in an email to me, “is that sometimes our drive to succeed, which we have to have to win, pushes our bodies to a dangerous place. I can speak from personal experience on this, because I did push too hard at Western States in 2006, and it put me in the hospital.”

How do we recognize when we’re going too far? Do we instinctively know? Twenty-five-time finisher and WS President Tim Twietmeyer learned this lesson quickly and says he’s only been close to self-destruction once in his 25 sub-24 hour finishes. “In 1982, I went from 168 pounds to 157 pounds and was in big trouble as I approached White Oak Flat,” he recalls. “I stopped there for 90 minutes to rehab the rig. I knew I had to stop or I wouldn’t make it the last 25 miles. That’s about as close as I’ve gotten to self-destruction.”

“WS is a bit unique in that it poses a variety of challenges, the most unpredictable being the heat and its impact on pace and performance,” Twietmeyer continues. “For me, the secret sauce at WS is handling the heat and still being able to run at peak capacity. Figuring out the metabolic game with hydration and electrolytes always seemed to be the toughest thing to get right. The training for the race and preparation is simple compared to getting the hydration plan dialed.”

If you’re a student of WS you know that Tim has arguably had the most impressive career at WS. He won (five times) when his best was better than everybody else’s that day. He never seemed to have to force it.

Things were different for Morrison at WS in 2006, an abnormally hot year. He didn’t see his problems coming the way Twietmeyer did in 1982. He was also a WS rookie with little 100-mile experience, but with a drive and determination that might not have been matched that day.

“I definitely was not the fittest or fastest runner out there that day,” Morrison recalls. “But I was so determined and solely focused on that goal that I was able to rise above my shortcomings.”

And oh how close he came.

Morrison’s body shut down when he entered the stadium in first place. Unable to complete the lap on the track under his own power, he was assisted by crew and pacers and later disqualified. He was hospitalized for 36 hours. His CPK count (a marker for how much dead muscle tissue is in the bloodstream) was measured at 450,000 at the hospital, as compared to the average WS finisher CPK count of about 15,000. A normal CPK count is 150-200.

Morrison’s bloodwork was studied by many and nobody has been able to give him an exact reason for why his body shut down 250 yards from the finish, but he has his own theory: “I believe that I collapsed once inside the stadium, because mentally I felt that I’d done it,” he says. “Physically, I think that I’d been on the brink since the climb up Robie, but mentally I was able to override the physical desire to pass out.”

What are the implications of pushing too hard? First and foremost, is our own health, but we also might consider the impact on our families and friends, the race organizers, the race, and the sport in general. If you have a partner or kids, do you want them to see you lying in the hospital with IVs sticking out of your arm? Sure, WS has the infrastructure to deal with just about anything, but is it good for the race to have people air-lifted off the course with hyponatremia (or to be hypothermic and wrapped in a shower curtain the way one pacer was while training for the race in 2008)? Our sport is growing and getting more and more attention. We have many more eyes looking at us.

What effect did renal failure after the 2004 Angeles Crest have on AJW? “These days I don’t think about the AC experience during races,” he says. “But I do bring it up in my memory in training so that I am sure to obtain a level of fitness which will prevent it from happening again.”

And what about Morrison? “For me that experience forced a great deal of character building, and I believe I’m a stronger person for it,” he says. “I’m hopeful that, as the saying goes, ‘What doesn’t kill you only makes you stronger.’ For as hard as we push ourselves and abuse our bodies, the human body is an incredibly resilient thing.” Brian is fine now and entered in the 2009 race.

I’ll end this with a quote from John Ticer, a three-time WS finisher and a guy who has run with broken feet and dislocated fingers. “There is no glory in pushing yourself to the point of near obliteration. Did you actually run a smart race if you are carried off to the medical tent and revived with I.V. fluids? I think not.”

What do you think?

This is the 3rd installment of the 2009 Western States Synchroblog Project. See what other ideas my fellow synchrobloggers have to make Western States better.

I wonder if depending on a prize for such thing somebody just simply won’t push themselves hard enough to be in best physical/mental state? What would be criteria?

@olga – Yeah, that’s why only the top ten horses can be judged for the Haggin Cup. I suggested the top ten men and women at WS. I guess it is possible that a top ten runner might sandbag for the prize but if you can run in the top ten at WS and still sandbag you are very good and very fit. Maybe it wouldn’t be a bad thing to reward that runner.

Good point on top 10, I agree if they sandbag and run that fast – way to go!

I remember sitting in the stands watching Brian come in. I had been on the trail patrol from Robinson to Michigan and managed to get a pizza and a six pack of beer on my way to the stadium. I was sitting next to an older couple, yes Craig, even older than I am, talking about the experience, how hot is was (is), etc. They had read about the race in the local paper and decided it would be interesting to see the finish. I attempted to impart on them why people do what we do. Finishing the pizza, working on the beer, Brian comes in. When he finally finished, the stadium was hushed, everyone looking at everyone else, wondering what we just experienced, and the couple turns to me, “does that happen often”.

I’d rather see a Haggis Cup. Full out Robert Burns for Breakfast on Sunday, including some nice single malt.

I talked to Jeremy Reynolds about this idea a few years ago. He (also a good ultrarunner) and his wife have won the Tevis/Haggin combo twice, which is quite a feat. He told me that the cup is given to the horse who looks best the day after completing the race.

Maybe a quick 5 or 10K race on the track should determine the winner of the running equivalent of the Haggin Cup trophy 🙂

Very good post Craig, thanks for all your research. I’m not fully convinced – However, a parallel argument might be that we ban drug use. Why? A person who chooses to use a performance enhancing drug is willing to risk their future health (among other things) for the sake of running faster. If we place performance above all other concerns for health then why do we stop at allowing folks to run themselves into the hospital? Why not go all the way and let them ruin other parts of their life?

For your consideration: Some smart dude could develop a relationship between finishing health and performance – the ratio being your “Haggin Cup Score”. For example If I finish with a 20hr time and have a CPK of 10,000 maybe I have a score of 200,000. Lowest score wins. This way the entire field could compete for the Haggin Cup.

Hey Craig,

Thanks for the great history lesson on the Haggin Cup,I remember my Dad talking about this years ago with some of his colleagues from Veterinary School.Dad worked at the M.B.check point when he was going to school at UC Davis,I know he worked 1959/60/61 and in one of those years they lost two beautiful horses on the climb out of El Dorado Canyon,this had a big impact on the race and my Dad,following that year he was against the race because of the extreme conditions and the increadible physical demand it put on the horses,he later changed his mind when he had an opportunity to talk with some of the horse people and see that it was more about training hard and racing smart,and of course non of these people wanted anything bad to happen to thier horses.

450,000 CPK….holy 4 letter word.

wow.

Excellent comments folks.

@SLF – I was there too because I wasn’t able to start the race due to injury. It was surreal. I do appreciate Brian being so open about what happened. And if you haven’t seen it, Brian posted the complete email he wrote me on his blog. Link is in the post above.

@Peter Lubbers – Didn’t we just hear that Jim Howard ran a couple 4:35 repeat miles the week after the 1983 race? And then a 2:20 marathon two weeks later? He wins the ultimate Haggin Achievement award.

@Dan Olmstead – Opening it up to whole field is an interesting idea. Gotta think about that one more.

@John Ticer – Thanks for sharing. I had asked a few horse people if they’d lost horses during the race but never got any answers – maybe they thought I was with the SPCA.

@MonkeyBoy – Yeah, that is by far the biggest number I’ve heard. Maybe some medical folks will chime in here.

Once the shock of reading Brian’s CPK wears off, I wanted to comment further.

I think this is an excellent idea to consider, especially considering the hostorical parallels between States and Tevis. I will be curious to hear from Twiet if his experience in 1982 didn’t shape the way he prepared and raced the next 23 times he competed at WS. Perhaps a Haggin mindset? It seems the better he prepared and managed his body in relation to the course, then he was able to start finishing much higher and running faster in his races.

As this race becomes more popular, so many folks seem to come here with an all or nothing mindset. Brian spoke about “drive”. I wonder if in pushing to get the most out of ourselves on race day, do we ever consider next morning, next week or even next race. I think we rarely do because 99.9% of the time, we know it’ll hurt a bit, but for the most part, we’ll be okay. I think one of the great equalizers with the 100 miler is the compete management of your effort, the course and your body and the systems that operate within it.

What a great idea for a post. Thanks for exploring this.

450,000 CPK! Yikes! Mine was 95,000 at AC in 2004 and that got me in the hospital for a week! I love the idea of the Haggin Cup. I have found that with each successive 100 miler I run I have been able to monitor my pain a bit more and keep things level as a result. Since my renal failure I have routinely had blood work done on the Monday following the race (certainly not the same as the immediate test after WS but not all races can do that kind of testing) and my numbers go lower each time. I do think a person can train themselves in to finishing the race well.

One last anecdote: In 2006 (the hot year when Morrison collapsed on the track) Tweit came from nowhere to finish in the top-10. In the weeks leading up to the race he had been talking about how banged up he was and how he was just going to try to make the 24 hour splits and have a good time. Well, he ended up running 20something and he and I were together doing the medical study interview after the race. In answering the questions from the interviewer it was remarkable to hear his recollection of the race:

Q: How many salt tablets did you take?

A: 22, one an hour and one extra at Devil’s Thumb

Q: What did you eat?

A: Some fruit, gels, stuff from the tables. That’s about it. I wanted a burger at Michigan Bluff but I was feeling pretty good so I just kept going.

Q: How about drinking?

A: About 50-60 oz an hour

Q: How do you feel now?

A: A bit tired but I need to shower and start handing out medals.

It truly was like he had just taken a walk in the park. Certainly Haggin Cup worthy!

Jiz

My “Haggin mindset moment”

JJ 100 MILER- I was on lap 5 running with some young guy (Joe Kulak)when I came in for aid,my wife of course asked me “when was the last time you pee`d?”….I don`t lie to my wife,so I looked at my watch and said,five hours ago.Your done was her reply.Well thats a problem because I did`nt feel done…..see ya later Joe….I needed to make a deal quick,so I told Sara that I would walk and drink until I started to pee again,she felt sorry for me and let me go.Well 45 min. later I was finally able to water a catus and start running,I caught up with Joe on the last out and back,unfortunately I was going out and he was coming back…..blah/blah/blah,anyway the moral of the story is,I walked away having made the right decision ( with the help of my wife) 2nd place 16:35.

Joe was nice enough to wait around for me and we enjoyed a burger and a beer together…..what a great day!

Hey, get a load of this. There was a Canadian who was also hospitalized the same time as me. He was so hyponatremic that he actually went into seizure. His CPK registered at Auburn Sutter Faith was upwards of 800,000. I’ve talked to him since, and he actually had some longer lasting health issues. He’s doing much better now. A lot of people I’ve talked to seem to think that those numbers aren’t realistic. All I know is that’s what they told me. Pretty crazy that they can get that high.

Craig, thanks for bringing up the history of the Haggin Cup. I was totally unaware of the award, and it’s a very interesting discussion. Thanks.

Brian,

Awesome to see you commented on the post and were willing to give Craig such a great interview. As dramatic as your story is I certainly know that we all would like to learn from it. And, I know I am not alone in saying I am really rooting hard for you to have success at this year’s race.

AJW

Andy,

I appreciate the encouragement. I’m really hoping to have a good race this year, and I wish the same to you and the rest.

So your CPK was 95,000 and you were hospitalized for a week? If I recall correctly, when Dr. Lind came to visit me in the hospital, he was a little skeptical of the numbers they were throwing around. It was due in great part to Dr. Lind’s assessment that I was released early from the hospital. The doctor who was assigned to me wanted to keep me in the hospital all week. Of course, I wanted nothing more than to just get home and get back to normalcy. When I told Dr. Lind that they wanted to keep me all week, he scoffed at the notion. He actually spoke with my doctor, and reluctantly they released me based on his expertise in the field of endurance athletics. He just directed me to keep drinking and peeing. I did just that and made a full recovery.

Brian,

A bit more detail. My 95,000 reading was taken on the Tuesday after the race (when I checked myself into the hospital). The reason I was there for a week was that I was suffering from Acute Renal Failure and therefore required extensive IV therapy. By Day 4 I weighed 203 pounds (my race weight was 165) and I needed to clear some fluids. By the end of the week I had received 34 liters of IV fluid (12 sodium bicarbonate and the rest saline). It is a week I will never forget and one I hope to never repeat.

Now, let’s get out there and train!

AJW

@John Ticer – I wouldn’t lie to Sara either.

@Brian Morrison and @AJW – Thanks to both of you for sharing your experiences – both in your emails to me and in the comments. As I understand it, two things have to happen for the CPK to get high: muscle death and dehydration (or insufficient fluids to flush the kidneys). Were your quads trashed while running at the end? Was that not incredibly painful? Or do you think the bigger contributor was dehydration or lack of peeing?

Andy, that’s pretty frickin’ scary stuff. I’m so thankful that I didn’t go into renal failure. Well here’s to no more race related hospitalizations!

Craig, I didn’t particularly notice my quads being shot during the race, but when I was released from the hospital, they were pretty buggered. As far as peeing, there were only a couple times all day that I stopped to relieve myself. I specifically remember talking to Dr. Bliss about that very thing, and her response was the peeing isn’t that great an indicator of over or under hydration. Her feeling was that when we are stressing our bodies like that, the urge to pee is often quelled.

Great discussion! As for me, my quads were totally trashed during the last 2 hours of AC in 2004. It was a bit like Brian’s experience in that I had a pacer pushing me up the hill to Sam Merrill (you know the place, where ultrarunners go to die:). Anyway, I gave it my all up to the aid station and then began the long, 4000 ft descent to the LA Basin. It is a sweet section of downhill singletrack that in normal circumstances would make you happy to be alive. However, that section for me was more like just trying to stay alive. Due to the muscle death I had going on brought on by an overly zealous climb up Sam Merrill I literally felt like someone was poking me with a dagger with every stride. It was brutal. Of course, I didn’t know how brutal until I peed at 6AM and it looked like coffee was floating around in the toilet…

AJW

@AJW and @Brian Morrison – Your candid discussions of such personal medical issues have been both educational and enlightening. Thank you so much for sharing them with all of us. This has been a great discussion!

Craig, these posts brought back memories of the “old days”. I worked with Doc Barsaleau at CRC and it was him that recruited Jim Howard into trail racing with the Levi Ride ‘n Ties. We used to crew for Howard when he ran with our friend, Jim Larimer. I’ve seen Jim Howard in RnT and WS100 crash with kidney failures. I think I’ve read he’s run more ultras and Ride n Ties than anyone else. He’s a horse (but not always smart).

Also, as aid station captains at WS100 Dusty Corners we always advised runners “in trouble” to be smart by stopping while they could so they could run another day. One SF-based experienced runner (sorry, can’t remember his name), decided to push on to the Last Chance medical checkpoint only to be driven back out to our area where a helicoper could medivac him to Auburn with his brain swelling. Scarry moment in WS 100 history.

@Judy and Luke – Hi! I should have assumed you’d know Doc Barsaleau.

Don Choi was the runner that was airlifted from Dusty Corners. I remember it very well and just told the story a couple of nights ago. As I recall we had him at our aid station for some time and then he was driven down to Last Chance because they had medical. He went into seizure I think and then driven back up to Dusty for the evac.

Yes, you’re right on the runner Don Choi. Thanks for clarifing the sequence.

I “think” I remember another horse incident that occurred in Auburn Lake Trails when Kathy Perry (a long-time Tevis competitor) lost a horse on the trail off the end of Shirtail Court (locally known as Roller Coaster Hill). I don’t think it was during the Tevis. I was just reading in the ALT newspaper advice on how casual riders need to prepare their steeds for trail riding the way runners need to get in condition for the trails. The article referred to the horses who’ve been wintering in the stables as “pasture potatoes” (like couch potatoes).

As for Max, I’ll pass the word to Grandma when I see her next week. Are you running this year? We’ll be traveling during WS but will follow the race on the internet.

Elevated CPK’s indicative of muscle damage: I wonder if the high WS CPK’s are in large part due to WS being a net downhill course. I’ve also wondered how post-Boston Marathon CPK’s compare to those at other marathons. Boston’s course is also net downhill, and is for many a quad trasher. One note: high CPK’s do not require dehydration. Indeed, they have been observed in cases of overhydration I’m not even certain that moderate dehydration puts you at increased risk of high CPK’s.

I had somebody else tell me this same thing privately. Perhaps I’m using the wrong term. If a 100 mile runner has enough fluid on board to maintain blood pressure, etc. but not enough to urinate more than a couple of times all day what is that condition called?

Please correct me if I’m wrong. If a runner is experiencing muscle necrosis but has enough fluid on board (or for whatever reason is able) to urinate frequently near the end of the race, would that not help flush out the “bad stuff” and result in a lower CPK level?

A few references for hyponatremia (all fluid overload) with rhabdomyolysis (= muscle death) are listed below.

Fluid on board and urination: You can have plenty of fluid on board, in fact way too much, and cease urinating. This is because the AntiDiuretic Hormone, Arginine Vasopressin, is released (Hew-Butler 2008). So you can’t rely frequency/quantity of urination to tell you about your hydration status. Consequently, *pushing* (drinking because you think it’s a good idea, not because you are thirsty) is potentially dangerous; hyponatremia has been known to develop following a race, via that route, aggressive post-race hydration.

As to whether flushing out is effective … Is it done because there is solid evidence that it is effective, or is it done because it seems logical?

Lulu Weschler

Hew-Butler T, Jordaan E, Stuempfle KJ, Speedy DB, Siegel AJ, Noakes TD, Soldin SJ, and Verbalis JG. Osmotic and Non-Osmotic Regulation of Arginine Vasopressin during Prolonged Endurance Exercise. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008. Jun;93(6):2072-8. Epub 2008 Mar 18.

Glace B, and Murphy C. Severe hyponatremia develops in a runner following a half-marathon. JAAPA 21: 27-29, 2008. (The person in this case study had CPK of 23,000 on Day 4 following the race.)

Korzets A, Ori Y, Floro S, Ish-Tov E, Chagnac A, Weinstein T, Zevin D, and Gruzman C. Case report: severe hyponatremia after water intoxication: a potential cause of rhabdomyolysis. Am J Med Sci 312: 92-94, 1996.

Trimarchi H, Gonzalez J, and Olivero J. Hyponatremia-associated rhabdomyolysis. Nephron 82: 274-277, 1999.

@Lulu Weschler – It’s just logical for me as I have degrees in computer science not physiology!

I’m not suggesting that a runner consume massive amounts of water to flush out the myoglobin and then become dilutionally hyponatremic. Let me give you a hypothetical example of what goes on in my head late in the throes of WS:

My pacer and I are at mile 85 at WS. We just passed a runner to move into 11th. We get on the scale at ALT and we’re at the same weight we started at 15 hours earlier. Good. I take inventory. Quads are ok but there is definitely damage. Feet hurt. Stomach on the edge so only coke and soup. We’re told 10th place is 5 minutes ahead. I really want that coveted top ten. Only one problem – I haven’t peed in 5 hours.

What do I do? I have some options:

1. Ignore the fact I haven’t peed in 5 hours and push hard to get 10th. My weight has been good so I am not “dehydrated.” Keep doing what I’ve been doing since I have no other major problems.

2. Keep going, but take actions to try to pee in the next hour. Drink coke at the aid station (fluid and carbs), soup (fluid and salt), and an extra cup of water. Work to consume my two 20 ounce bottles of water in the next 5 miles to Brown’s Bar. Continue taking gel that has sodium. I decide to not take anymore S-caps to hopefully entice my body to just shed a little bit of the water it’s holding onto. Once I pee I’ll go back to S-caps.

3. I could get an IV at ALT and drop out of the race.

So, obviously, I choose option #2. Continuing with my hypothetical example, I don’t pee by Brown’s bar despite drinking my two bottles of water, but I’ve had the urge twice only to be fooled (it’s memorex). I do coke, soup, and water at Brown’s Bar. Still in 11th place with 10th still 5 minutes ahead. On the climb to the upper quarry I feel the urge to urinate and am able to release a very satisfying amount of hot yellow urine. YES!! Now I feel a whole lot better about pushing the last 8 miles and grab that 10th spot.

Oh, and thanks, Lulu, for the references.

At 85 miles, with the same weight as at race beginning, you are most likely water overloaded. Overload likely has nothing to do with salt intake (although it may be possible, as there are grapevine stories of people ingesting huge quantities of sodium). Much more likely due to AVP having been released, in which case, any additional fluid you ingest will also be retained. So those 2 x 20 ounce waters are the last thing you want! Sure, pick up stuff at the aid station; always have stuff available; here, a delicate balance between lugging stuff in a very intense race, and what you might desperately need. But I can’t imagine you’d either need or want to drink one drop before Brown’s, and I wouldn’t be surprised if you drank nothing before the finish, and were fine with that.

As to getting urination started … it is 8PM, so the day is cooling. This seems to be a trigger to stop the AVP release. Once this happens, it won’t be long ‘til blessed relief. AVP half-life is quite short, maybe 6-10 minutes. Something about cool that tends to slow down AVP release. Large volume of urine confirms that you had too much water on board.

I don’t know what soup you got at Brown’s, but there are many soups which, depending on how they are made-up, how much water is added, are very concentrated in sodium. This may trigger urination. Mechanism: sodium is quickly absorbed, so you quickly have blood plasma with higher osmolality than the surroundings it passes through. Therefore, water is drawn into the bloodstream (via the capillaries). Increased blood volume gets to the kidneys, and if AVP has vacated the scene (AVP was telling the kidneys to re-circulate rather than excrete the water), the kidneys will happily excrete the water. Remarkable how quickly people urinate in these situations. Notice that in this case, sodium has been the remedy, not the culprit! This, by the way, is a major reason why hypertonic saline (3% or 5%) and *not* Normal Saline (0.9%) is the proper treatment for hyponatremia (Hew-Butler 2007, 2008 “Practical…” Moritz 2008, Siegel 2007).

To repeat, taking on water weight is much more likely to be the result of high AVP levels. Very well known that AVP is released for reasons other than the prime physiological reason, which is the need to conserve water, as mainly signaled by increasing osmolality). Recent evidence that AVP release is a feature of long races (Hew-Butler 2008 “Osmotic…”). The essential point is that during WS, you can expect a surplus of AVP, and consequently, your margin of error in the overhydration department dramatically tightens up. Urination won’t be there to dump any in excess of need, and the best guess is that that is why you are overhydrated, have not dumped what you don’t need. Remedy is to not drink too much in the first place.

A Normal Saline IV at that point? Absolutely not!

–Lulu Weschler

Hew-Butler T, Jordaan E, Stuempfle KJ, Speedy DB, Siegel AJ, Noakes TD, Soldin SJ, and Verbalis JG. Osmotic and Non-Osmotic Regulation of Arginine Vasopressin during Prolonged Endurance Exercise. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008.

Hew-Butler T, Anley C, Schwartz P, and Noakes T. The treatment of symptomatic hyponatremia with hypertonic saline in an Ironman triathlete. Clin J Sport Med 17: 68-69, 2007.

Hew-Butler T, Noakes TD, and Siegel AJ. Practical management of exercise-associated hyponatremic encephalopathy: the sodium paradox of non-osmotic vasopressin secretion. Clin J Sport Med 18: 350-354, 2008.

Moritz ML, and Ayus JC. Exercise-associated hyponatremia: why are athletes still dying? Clin J Sport Med 18: 379-381, 2008.

Siegel AJ. Hypertonic (3%) sodium chloride for emergent treatment of exercise-associated hypotonic encephalopathy. Sports Med 37: 459-462, 2007.

@Lulu Weschler – Thanks for making me think!

Remember that what started this discussion is that I want to urinate to flush my kidneys. The goal is to pee, so a large volume of urine is GREAT! Do I know that this works to flush the myoglobin? I can’t site you any research except my personal experiences as a 100 mile volunteer (about 10), crew (about 15), pacer (about 15) and finisher (10), and RD of a 100km (7). I’ve got 5 finishes at WS and CPK never higher than 5100 (at least the last three as I was chicken to get the blood draw on my first two). Never needed an IV, never hospitalized.

Maybe my hypothetical isn’t fair because it doesn’t include what I’ve done all day. Like I said, things are good except for lack of peeing the last 5 hours. That means I’ve taken care of myself. The soup is what I’ve been doing since about Michigan Bluff or Foresthill, along with taking S-caps all day and drinking Gu2O. I’ve done a good job of monitoring my electrolyte consumption all day. My weight has not been far from my starting weight all day and it has never been above it. There are no signs that I’ve not had enough sodium (no cramps, no sloshy stomach, etc). But I want to pee.

So why am I not urinating? Have I reached a balance point between electrolyte/fluid intake and sweat rate? Or is it AVP as you suggest?

If is the former then if I continue to take in the same amount of fluid and electrolytes the last 15 miles I might not pee till the race is over. The only thing I do differently at 85 miles is I cut back on the sodium (cutting back on the S-caps which I’ve been taking all day) and switch to two bottles of water and concentrate on drinking both – which often gets harder towards the end of 100 miles. By drinking water only and reducing the amount of sodium (not stopping altogether) that should, in my simple logical mind, allow the body to reduce the volume (to maintain the proper sodium concentration in the body). As a result, I pee.

If it is AVP as you suggest then as soon as it stops being released (maybe because of the cooler temps) then I’ll just dump the fluid I’ve consumed from ALT to Brown’s. I will pee.

I do hope you didn’t just suggest that I stop drinking the last 15 miles of the race! Yikes!

In no way did I mean to suggest that you stop drinking in the last 15 miles of the race. I was speculating, though, that it *might* be possible that you did have enough water on board to get you through those miles, and strongly.

Nor did I mean to imply that logic doesn’t work! I should have said “apparent logic.” Logic in physiology is often hidden, but of course it works!

More later,

and thanks for including me in this discussion,

Lulu Weschler

Flushing and CPK, the original question. Your experience is very important. And there most certainly is an apparent logic to hydrating to flush. So there you are, in the field with real situations, and what are you to do? Exactly what you do, go with your experience which by the way is accepted by many. The very idea of experimenting … (let’s see what happens if instead we XXX) … is hideous. Still, you have to wonder, is there a better way? Experiments do get done, inadvertently, and so we have to scour reports of what happens when high CPK is treated differently, or for that matter, not at all.

To me, there are little hints, things that don’t ring quite right, that beg questions with respect to both aggressive hydration for high CPK and NS IV’s for myoglobinuria are the best way to go. There have been many people with post-race high CPK. Did the ones who aggressively hydrated, towards the end of the race and immediately post-race, clear any faster than those who didn’t? Also, kidney physiology (about which I am *not* in any way expert) makes me wonder: is flooding the optimal way for clearing stuff, consistent with how the kidneys work? Is there either benefit or adverse effect of increasing hydrostatic pressure (glomerular pressure) when there is CPK to get rid of (or myoglobin!)? And on the myoglobinuria front, must we accept the gross swelling/weight gain associated with NS IV treatment of myoglobinuria as part of the only way to deal with that problem? (This swelling, by the way, has nothing to do with hyponatremia, as what’s pumped in has essentially the same osmolality as what is there. What happens is that the IV fluid leaks out of the blood stream into the surrounding areas, or interstitium. This happens because inflammation makes capillaries more permeable, and the increased hydrostatic pressure of the IV fluid pushes plasma out.)

Is there a better way? Here is a parallel history. In the early days, hyponatremia, then called “water intoxication,” was treated with hypertonic saline HTS, 3% (Wynn). But subsequently there were deaths due to errors in how the HTS was used. Medical people therefore turned to using Normal Saline NS. Thus, by the 1980’s, hyponatremia was mostly, but not exclusively treated with 0.9% NS. However, with NS as the treatment mode, there have been several deaths, cases with worsening symptoms, and a number of instances of people being in coma for days. But then you think, the illness of hyponatremia is so severe, so life-threatening, death is expected in some, so you get no clue that NS is the wrong treatment. You only know if you find that an alternative that gives better results. Fortunately, HTS was still being used here and there, and has shown itself to be the correct choice (Davis, Hew-Butler and refs in a previous posting, Moritz, Siegel. Also, check out the story in Noakes from the 1986 Chicago 50 miler).

Finally, we should still think about how do you get high CPK in the first place? Does CPK level correlate with hydration status? I am aware of no study that staying topped up on water means you will have less high CPK values. What is known to lead to high CPK: (1) eccentric exercise, like you do with quads in downhill running, and (2) lack of training.

–Lulu Weschler

Davis DP, Videen JS, Marino A, Vilke GM, Dunford JV, Van Camp SP, and Maharam LG. Exercise-associated hyponatremia in marathon runners: a two-year experience. J Emerg Med 21: 47-57, 2001.

Hew-Butler T, Ayus JC, Kipps C, Maughan RJ, Mettler S, Meeuwisse WH, Page AJ, Reid SA, Rehrer NJ, Roberts WO, Rogers IR, Rosner MH, Siegel AJ, Speedy DB, Stuempfle KJ, Verbalis JG, Weschler LB, and Wharam P. Statement of the Second International Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia Consensus Development Conference, New Zealand, 2007. Clin J Sport Med 18: 111-121, 2008.

Noakes TD, and Speedy DB. Case proven: exercise associated hyponatraemia is due to overdrinking. So why did it take 20 years before the original evidence was accepted? British journal of sports medicine 40: 567-572, 2006.

Wynn V, and Rob CG. Water intoxication; differential diagnosis of the hypotonic syndromes. Lancet 266: 587-594, 1954.

@Lulu Weschler – I talked with several of the doctors associated with WS and they all seem to agree. Here is what one of them wrote to me in an email:

And there should be a comprehensive article by Dr Lind in one of the upcoming issues of Ultrarunning.

Dr. Lind has contributed a great deal of work and thought on this issue. The questions that remain do not reflect on his contributions, but rather on the stubbornness of the problem. I look forward to his upcoming article in UltraRunning; I have his UR article from some years back, with CPK ranges for numbers of subjects.

Is there correlation between immediate post-race CPK’s and hydration status, both through the race and at the time Dr. Lind does the measurement? Is there correlation between CPK’s and finishing times? The weather that day? Plasma sodium concentration?

Before Dr. Lind’s was measuring post-race CPK’s, wouldn’t they have been elevated? If so, how do post-race CPK’s progress over the next few days in those who aggressively hydrate and in those who hydrate according to how they feel, allowing thirst to drive their intake?

Back to the 85 mile scenario, weight maintained, no urination in 5 hours. Why, with a likely surplus of water on board, you haven’t urinated. We know that AVP’s are up in races; is there a better explanation? Why then would you force fluids, which will be likely be retained (unless the cool of night saves you) and thereby flirt with the illness of hyponatremia?

–Lulu Weschler