I remember the first time I stood in the pre-race check-in line in Squaw Valley in June of 2001. I met a veteran runner who was more than willing to give this first-time Western States runner advice. We talked about all sorts of course specific things like the heat and how to stay cool, what to expect on the climbs and descents, etc. But, what has stayed with me to this day were his strategies on how to avoid the medical folks at the aid stations who had the tools and authority to force runners to rest or pull them from the race. He stressed the importance of getting a low starting weight by: not eating breakfast or drinking on Friday morning; taking your shoes off before hopping on the scale; and watching to see if there were scales that were giving “better” readings.

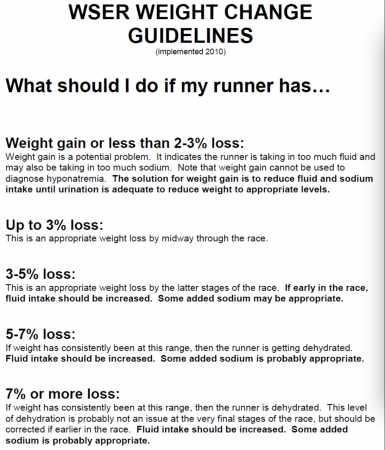

Your “starting” weight was written with indelible ink on your wristband, along with your Friday pulse and blood pressure. The tools at the 10 or so medical aid stations were the scales and the 3%-5%-7% rule. When you came into an aid station you had to first get on a scale before doing anything else, and the medical volunteers would look at the number on the scale and compare it to the number on your wristband. A 3% drop in weight would usually warrant a warning to drink more fluids, a 5% drop meant you had to stay at the aid station until you were back below 5%, and a 7% or more drop from the number on your wristband could result in withdrawal from the race or a lengthy forced break.

My veteran friend in the check-in line also gave me advice on how to weigh heavier at the aid stations, completely opposite from the pre-race weigh-in. He said to try to be as wet as possible before coming into the aid stations by pouring all the remaining water in my bottles on my clothing, or to douse in creeks. He said if my weight was low I could tell the volunteers that my starting weight was not accurate. All these seemed really silly to me but then he revealed to me that he would put rocks in his pockets if his weight dropped too much. WTF?

These protocols and practices, which stayed in effect at Western States through 2009, created a strange relationship between medical volunteers and runners. They also likely caused runners to force drink and thus overhydrate. Fortunately, starting in 2010, things began to change. Runners anecdotally knew the scales and subsequent weights were not reliable. The research, primarily done at WS, also began to reveal that gaining weight was a more serious issue because of exercise associated hyponatremia (EAH).

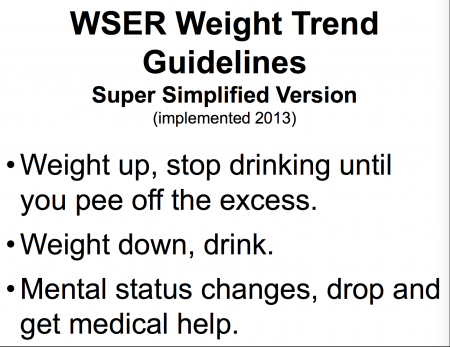

It soon became apparent that a single data point of weight change (either increase or decrease) was not a reliable indicator of occurrence of EAH or whether a runner would get to the finish line. If accurate weights could be obtained, and weight trends were used, these trends could be useful to knowledgeable athletes. They may also be helpful to medical volunteers in diagnosing and treatment. But in practice that wasn’t realistic.

By 2015 WS only had scales at the start and finish line and their use was optional. By 2016 scales weren’t anywhere at the race unless needed for research projects. The advice given to runners is to drink to thirst to avoid overhydration and to avoid excessive use of supplemental sodium which can drive the thirst mechanism. The role of the medical volunteer is to observe the mental status of the runner. To look them in the eyes. To be their advocates. To help runners fix any issues by giving good sound advice based on evidence-based research. Aside from serious medical issues or trauma, it’s ultimately the runner’s responsibility and decision to call it quits when things aren’t going well.

With roots based on endurance riding where horses are unable to tell others how they are feeling it’s not surprising WS adopted a similar philosophy initially. Dropping the scales and putting the responsibility back on the runners was a major shift in philosophy for WS. This is not meant to be an indictment on the past, but rather a good reminder that we need to stay open-minded and continually adapt and evolve our medical protocols to help runners get safely to the finish line. As my predecessor once told me, “sometimes change is … ok.”

I sure don’t miss those scales.

For more information about the science and research done at WS please see https://www.wser.org/research/scientific-publications/

Today, four other bloggers are joining me in writing about what’s changed in the sport since 2009. Read what they have to say.

- Scott Dunlap writes about the growth of the sport

- Wyatt Hornsby on the changes at his favorite Leadville 100

- Andy Jones-Wilkins laments over the loss of minimalism

- Sean Meissner on GPS watches and Strava

I don’t miss knowingly loading up on fluid coming into AS trying to “beat” the scales and knowing that a Medical Lead, who might be a chiropractor, could start or stop you based on your numbers, not your mental or conscious state. The “loading up” can lead to other problems well documented and the underlying culture of deception vs. science has been Thankfully outgrown.

Pingback: Ultramarathon Daily News | Wed, Feb 20 | Ultrarunnerpodcast.com