A couple of months ago my wife and I were enjoying a nice meal outside on the deck of a beautiful home overlooking the McKenzie River. It was a business meeting of sorts, mostly with people who work with my wife in technology and education. The conversation, as is usually the case in these types of get-togethers, quickly turned to ultras. My wife and I had just helped out at the Pine To Palm 100 miler in Ashland, OR where we ran an early aid station, and I worked the 2am to 6am shift at the finish line as a ham radio operator. The week before that we each had run McKenzie River 50K so there were lots of stories to tell from many different perspectives. One of her colleagues mentioned that my wife was taking a ham radio class. Without flinching, one of the spouses who works in “communication” at the UO said, “That’s funny, I’m taking a smoke signal class.” Laughter ensued.

While I probably shouldn’t have been surprised that ham radio equated to delivering messages via smoke signals to a guy who works in high tech communications, it did strike me that what I do on the weekends is obviously very different than what he does. I tried to explain that ham radio is alive and well and used all the time to support events and rescues in the mountains. That all of the new modes and methods of communication he works with are reliant on access to a functioning internet or other permanent infrastructure. That ham operators come with their equipment and set up a complete communication infrastructure in a short period of time. But, eventually I just let it drop, and the conversation quickly moved to cloud computing, iPad/iPhone apps, or something equally as cutting edge and modern. Ham radios? They still do that?

If you’ve run an ultra in the mountains you’ve probably benefited from radio communications, either on the professional or amateur frequencies. Professional frequencies are purchased through the FCC and used by police, fire, forest service or other government agencies, and commercial enterprises like ski areas. At Waldo 100K we make use of the professional frequencies used by the ski patrol, and we also benefit from the dedicated and passionate support of about 30 amateur (generally referred to as ham) radio operators from two groups: Lane County Sheriff Amateur Radio Operators (LCSARO) and Valley Radio Club. Their leader is Matt Dillon. No, not the actor, but a man with more than 50 years of radio experience who wears a red hat emblazoned with “W7ARD”, his vanity call sign licensed to him by the FCC.

What do the ham radio operators do at Waldo? They come with all their cables, antennas, batteries, repeaters, radios, etc., and setup a complete communication infrastructure that covers the entire course, a broader area than our ski patrol radios can reach. They recruit and staff all the operators needed for each aid station and the many shifts required to cover the 18 or so hours at the finish line. They are self-reliant and need little to nothing from us, except an event. They help us with the following:

- Emergencies. For example, if someone were to become injured or ill and needed to be evacuated, the ham radio operators would provide the communication lines to facilitate that evacuation. If the injured person was immobile, we could send a ham radio operator in with other rescue personnel so we could maintain contact.

- Problem Solving. Hams have helped us solve many problems over the years. This could be as simple as figuring out how to get extra ice, coke, or GU to an aid station that needs it to something more serious like discovering and correcting course sabotage. Because radio transmissions are broadcast, other operators (and even people with scanners or radios not associated with the race) can also hear the transmissions. For example, in 2007, the year Waldo was sabotaged, the lead runner was sent off course with at least 30 others. He was still unaccounted for between the 3rd and 4th aid stations long after all the other lost runners got back on course. The first intersection where the 30 had been directed off course was “fixed” by another runner (actually, The Queen herself), and despite reports from her and others, we still didn’t know the extent of the vandalism and where he might be until one of the ham operators who was hiking into a later remote aid station came across him running in the opposite direction he was hiking, a good four miles off course. The operator had heard all the radio traffic so he knew we were looking for this runner. He turned the runner around, and the information that we got from his location and direction helped us figure out what had happened. He had gone through a second vandalized intersection that sent him even further in the wrong direction. With the new information we were able to locate and correct three other intersections that had also been vandalized, averting what could have been a major catastrophe.

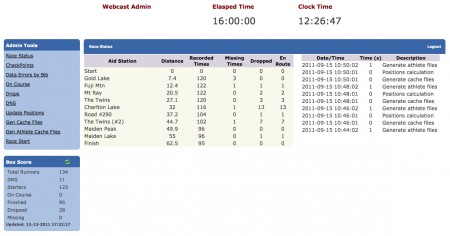

- Tracking Runners. Runner bib numbers and times are recorded at each aid station and transmitted to “net control” where the master database of every runner is maintained. When the sweeps come to an aid station a reconciliation of runners occurs. If all runners are not accounted for, we (race management) have to figure out where the missing runner is. We also used this data this year to feed the online webcast through ultralive.net, but I’ll write more about that later.

Could we accomplish the same objectives with cell or satellite phones? Yeah, probably to some extent. But, even if we had great cell coverage, which we don’t, the broadcast nature of voice radio is much more powerful than one-to-one communication via phone, especially during emergencies. The cost is also a consideration. Satellite phones are still not cheap, and ham radio operators work for nothing – their amateur licenses don’t allow them to work for pay. While we can and do give their clubs the occasional donation to help offset the cost of equipment, they do not and cannot charge for their services. The same goes for chips or GPS for tracking runners and meeting objective number 3. At this point, the technology is still prohibitively expensive for most ultras, but I expect we’ll see “advances” here in the very near future.

So why do the ham operators work our race? Matt says amateur groups use events such as Waldo to practice and hone their skills. That’s good for all of us in the county as they help support SAR and other county missions. Perhaps more importantly, when and if our normal communication infrastructure fails to work, they will be called upon to setup and provide emergency communication. And, they also like to give back. As Matt says, “Working at Waldo is a way to benefit others with my hobby of 50 years. I know that our communications efforts enhance safety for the race participants and make the management of the race more efficient.”

We are very grateful and appreciative of the 30 or so ham operators who work at Waldo, and I couldn’t imagine directing this race or any race in the mountains without them.

Waldo is a relatively simple race in terms of ham radio infrastructure. Although we upgraded to multiple repeaters in order to spread out the radio traffic this year, we can actually cover the entire course from a single repeater location – Wolf Mountain. A repeater, which can be owned by a group or an individual who usually let other amateurs use it, is basically an unmanned device that is positioned on a high point (a mountain), receives radio signals on a frequency, boosts up the signal, and transmits it back out on another frequency. This allows for communication over a much wider area than just simple line-of-sight communication (such as when you use family or CB radios). Radios are programmed to send and receive on the frequencies of the repeaters (fixed or portable) that are used at the race.

The ham radio infrastructure at Western States 100 is significantly more complex than Waldo’s (http://comm.wstrail.org/). It is the result of many years of tweaking and supporting both the horse race (Tevis) and the running race (WS). Ralph Lucas (W6RWL) has been the leader of the “comm” folks at both Tevis and WS since 2004. He puts in about 40 hours/month from August to May and 40 hours/week for June and July. He estimates that on WS race day about 125 operators and $185,000 in equipment, including 17 repeaters, are used to setup and track runners from the start at Squaw Valley, through the high country, deep in the canyons, through the river crossing and the horizontal canyons to Net Control at the Auburn Dam Overlook. Both races have mounted sweeps who are also licensed ham operators. In all, there may be 150 ham operators working in some capacity on race day.

With a race like WS that has resources beyond almost all other ultras, you and my smoke signal friend might think other technologies would be used to track runners. Tim Twietmeyer (KG6UHV), former WS Board president says, “We have a communications team that tries to move a bit forward every year. Over the years, we’ve tried to use other means to track runners (electronic mats), but ham radio seems to be the best option. It has room for error in numbers, but generally it’s reliable. We’ve taken the money we’d pay for someone to track runners with chips and given it to the ham guys. That way they can develop the comm capabilities in the canyons and we can also use it in a disaster scenario (like a fire or rescue that has nothing to do with the event).”

That said, WS does employ many different methods of getting runner split info into the live webcast, from laptop computers connected to the internet, to smart phones, to digital ham packets (WinLink200), but the majority of aid stations still use ham voice to transmit bib/split pairs to Net Control where they are entered into the webcast. The webcast system, just like the ham infrastructure, has evolved over the years. The current system is ultralive.net, developed by California ultrarunner and software guru Ted Knudsen. Ted, who ran his first WS in 2006, recalls, “My mother-in-law was watching me during the day via the webcast, but there were no updates after 7am until about 11am so she thought I had dropped (I finished just before 9am). So I was determined to help out the next year.” After helping in 2007, he developed a newer, more modern system based on Web 2.0 technology.

The new system was ready to go in 2008, but the race was cancelled due to fires. In 2009 the system was still being hosted on ws100.com, a shared server. During the race, which Ted was running, the site was quickly overwhelmed by the traffic and automatically shutdown thinking it was being attacked (denial-of-service). After that unfortunate debut, Ted was determined to build a system that could handle the traffic – ultralive.net received 1.5 million hits during the 2011 event! Perhaps a bit over-engineered, it is now hosted on the Amazon cloud and employs sophisticated caching methods so the database doesn’t need to be queried for every hit. Data can be entered via a web browser on a laptop or desktop computer or via the mobile version on a smart phone. For those locations that have internet capabilities, the data can be entered directly on location. It’s still not chip or GPS tracking, but there are many fewer points for errors to be introduced.

We used ultralive.net this year at Waldo (http://ultralive.net/waldo/webcast.php), and it worked extremely well. We used ham voice to transmit all bib/split pairs from nine checkpoints, and had two people entering data at the finish. It was a success, not only for people watching their runner or the race, but it also served as our runner tracking database. The tools are powerful and allow management to track DNS, DNF, missing runners, etc. If you are the RD of a 100 miler, Ted is making you this offer: “From the start, I designed it for all 100 mile races to be able to use it for free. There are a lot of WS100 specific features, but I also made it general enough to work with just about any race.” On behalf of the whole ultrarunning community, thanks, Ted.

Does this get you interested in taking a ham radio class and getting your technician license? If so, look for a radio club in your area where classes are offered and the tests are administered. You can get a technician license by passing a 35 question test that costs $15 to take (the book is $30). The license is good for ten years. If this doesn’t entice you to get a license perhaps next time you’re at a race you’ll be inclined to go up and talk to and thank the ham radio operators for their efforts. Or when you’re anxiously watching a webcast from home you’ll have a better appreciation for what it takes to get that information to the screen in front of you.

73, KF7IMJ

Cool, insightful post. Again, another reminder of all that goes into an event. But also another “layer of community” that makes Ultra running special — bringing folks of “all kinds” together, and the mutual respect and support that develops.

OOJ, lots of people come together to make these events happen, and most of them have never run an ultra in their lives and never will.

Thanks Craig for another informative post. I echo OOJ in my appreciation for all the volunteers that put in numerous hours so that a few of us can run safely what most would consider a ridiculously long distance over challenging terrain. Thank you, thank you, thank you… Happy Holidays!

John, glad you found it informative. You gonna go get your ham radio license now?

really interesting post, thanks Craig (and Ted!)

Brett, it was really cool seeing Ted get a WS Friend of the Trail award last year. His contributions to the race and the ultrarunning community have been significant.

Thanks for posting this. It’s so neat to hear about all the great work and great people that make ultras happen. I think it’s so easy to take these things for granted especially in areas like communication, trail work, and medical. Keep ’em coming. Thanks again!

Thanks, Alex. I agree, it is easy to take these things for granted. I do have a couple more ideas along these lines that I’ll write about next year.

I just came across this article from 2011, and I can testify that I personally kept those ham operators at their posts for well over 18 hours, and belatedly apologize and thank them (and you).